The moment of truth for the planet that might resemble Earth: does TRAPPIST-1e have an atmosphere?

The moment of truth for the planet that might resemble Earth: does TRAPPIST-1e have an atmosphere?Exoplanet TRAPPIST-1e currently offers the best chance of finding out whether Earth-like worlds around small stars can be habitable. New observations from the James Webb Space Telescope may provide the answer.

“There are two possible outcomes, and both are enormous,” says astronomer Natalie Allen in a video call from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Next to her, Nestor Espinoza, her supervisor and co-leader of their research team, nods in agreement. They are working on one of the most ambitious projects of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): the search for an atmosphere around the rocky planet TRAPPIST-1e. The first four observations have now been taken and two papers have been published, but the biggest question — does this planet have an atmosphere? — remains unanswered for now. Just a little longer, not much. Fifteen new Webb observations scheduled for the coming year should settle the matter.

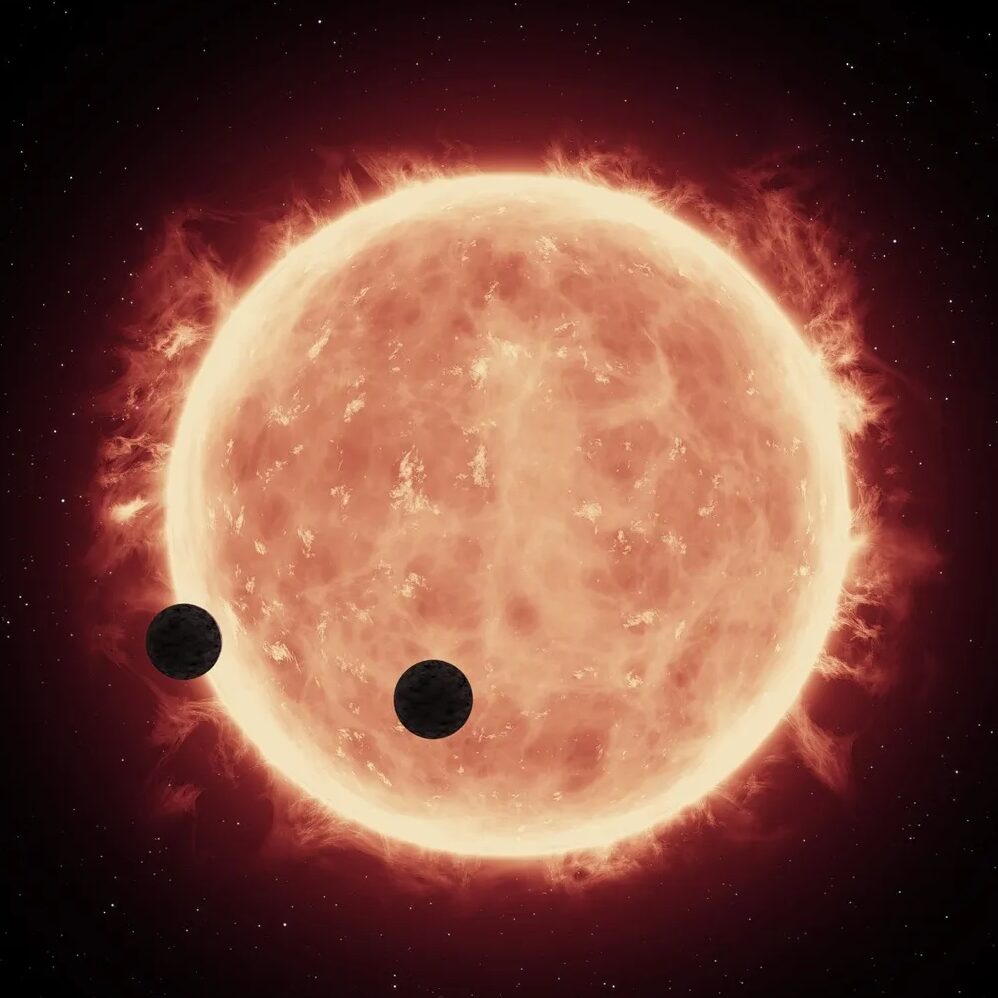

Exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than the Sun) are found around nearly every star; thousands have been discovered in recent years. Among them, the TRAPPIST-1 system stands out as one of the most evocative discoveries. It is a miniature version of our own Solar System: seven planets, all roughly Earth-sized, orbiting a small red dwarf star. In our Solar System, the entire system would fit inside Mercury’s orbit. It was discovered in 2017 with TRAPPIST, a pair of telescopes developed in Belgium (hence the name; the successor is called SPECULOOS). The world reacted euphorically. If a second Earth existed anywhere in the cosmos, surely it had to be here.

Crown jewel

Within this compact system, TRAPPIST-1e is considered the crown jewel: slightly smaller than Earth and located in the “habitable zone,” the orbital belt where liquid water can exist. The term does not guarantee habitability; that depends on the presence of an atmosphere, which determines how much heat a planet retains and what its climate is like. Our own Solar System illustrates this vividly. Venus, Earth, and Mars all lie in the habitable zone, yet could hardly be more different. Venus has a thick atmosphere, and its surface is scorching hot. Mars has lost most of its air and is a barren desert. And Earth? Without an atmosphere, the average temperature here would be about twenty degrees below zero. Only with a stable, protective atmosphere does a planet become a potentially habitable world.

TRAPPIST-1e therefore carries a particular burden. Not because our hopes of finding extraterrestrial life depend on it, but because this world is a test case: can small rocky planets around red dwarf stars hold on to their atmospheres? Co-lead researcher Espinoza puts it concisely: “This is it. This is the key system with which we can test this question.”

TRAPPIST-1 is a red dwarf star, the most common type of star in the Milky Way. Red dwarfs are small (TRAPPIST-1 is about the size of Jupiter), cool, and ten times more numerous than Sun-like stars. That makes them appealing targets for planet hunters: around a small star, even a thin atmosphere casts a noticeable shadow.

Of the nearly four hundred known planets around red dwarfs, a large share lies relatively close to Earth. The closer a star is, the more of its light our telescopes receive — and the more precisely we can measure tiny variations. TRAPPIST-1 sits at a “comfortable” forty light-years: close enough that, in principle, the atmosphere of a rocky planet could be detected.

But red dwarfs have a downside: they are active. They eject bright flares and UV and X-ray radiation that can strip away a fragile atmosphere. In addition, planets orbit so close that they become tidally locked: one side in eternal day, the other in eternal night. Only a stable atmosphere can moderate such extremes.

Litmus test

For that reason, TRAPPIST-1e is a true litmus test. If this planet, around this star, at this distance, turns out not to have an atmosphere — what would that mean for all the other Earth-like candidates around red dwarf stars?

The existence of an atmosphere around a distant planet can be established using transmission spectroscopy: when a planet passes in front of its star, its atmosphere filters out a tiny fraction of the starlight. That missing light — sometimes only a few thousandths of a percent — contains the fingerprints of molecules such as CO₂, water, or methane. To distinguish these wisps of signal, the telescope’s detection limit is pushed to the extreme. Espinoza: “We write our own scripts to process the Webb data, because the standard software isn’t designed for signals this small.”

The first four transits of TRAPPIST-1e produced a clear non-detection: the characteristic “bump” that CO₂ would create in the spectrum is absent. A Venus-like, CO₂-rich atmosphere therefore seems very unlikely. A thin, Mars-like atmosphere also fits poorly with the data. Ana Glidden of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, lead author of the atmospheric-interpretation paper, says: “The observations do not rule out nearly as much as one might think. For example, it is still possible that there is a global ocean on the surface. But we can confidently say that a thick or thin CO₂ atmosphere is not likely.” Other scenarios remain viable: a bare rocky planet, a nitrogen-rich atmosphere like Earth’s, or a hazy smog atmosphere like that of Saturn’s moon Titan. “A habitable planet is still among the possibilities,” Glidden adds.