Moon science with a conscience

Scientists play a major role in the plans for moon exploration and use. In Teylers Museum, they are considering a new responsibility: how do we deal with a celestial body that was never ours, but has shaped us?

‘It’s your fault, Marc!’ shouts emeritus professor of history Klaas van Berkel from the side of the room, his finger pointed at astronomer Marc Klein Wolt. ‘Scientists are the first to think they have to do something on the moon. So they are also the first to pollute it.’ Laughter breaks out, but the teasing slur lingers – like an uncomfortable truth that is difficult to brush aside.

On 20 June, a diverse group of around forty scientists, artists, lawyers, philosophers and former diplomats – from astronaut André Kuipers to artist Esther Kokmeijer – gathered at Teylers Museum in Haarlem to discuss the establishment of an Embassy of the Moon. A platform that is not primarily about technological progress or knowledge development, but about the question: what does the moon mean to humanity and how can we treat it with care and respect? Because although the moon has been a distant source of imagination for centuries, human activity on its surface is increasing rapidly. New missions by the US, China, Russia, India and Europe are in preparation, with plans for permanent bases and research facilities. This raises profound questions about ownership, use and protection of our natural satellite.

Scientists have traditionally been the driving force behind lunar exploration. From Apollo to Artemis, science was the official motivation. Now, on the eve of commercial exploitation, scientists are once again the first to be able to set a course – towards careful and sustainable use. Many feel that responsibility. When Marc Klein Wolt visited a performance by theatre maker and writer Marjolijn van Heemstra about the colonization drive for the moon, she unexpectedly pointed him out: wasn’t he planning to build something there himself? ‘I had never considered that my scientific plans on the moon also entail responsibility,’ he says. ‘That realization gave us the idea to discuss this with a broader group.’

Although much of the lunar research can be done remotely, there are crucial questions that can only be answered from the surface. In short, it revolves around three pillars: the history of the moon; the moon as a unique window on the universe; and its environment, with a view to habitability and use.

‘We have only been to a small part of the lunar surface so far,’ says planetary scientist Wim van Westrenen, who specialises in the evolution of the moon. ‘It is like walking around the Netherlands and trying to understand what America looks like, without ever having been there. That doesn’t work.’ For him, the holy grail is to find ‘pieces of Theia’ – the planet that, according to the most common theory, collided with the young Earth and thus created the moon (or rather the ‘Earth-moon system’).

During that collision, the Earth’s axis tilted, which had a major impact on seasons and climate stability. The Earth’s rotational speed was also determined – and thus the length of our days. In addition, the moon causes the tides, which contribute to ocean currents. All these effects make it a life-determining factor in the origin and survival of life on Earth.

At the same time, the moon is probably the result of a chance event. This makes us think about how special life on Earth is – and how rare such circumstances may be elsewhere in the universe. For Van Westrenen, unraveling that story is not just a scientific quest, but an existential one: ‘The history of the moon is the story of our own origins.’ It is not without reason that he calls the lunar surface a fossil of the early solar system – a virtually intact archive of meteorite impacts and other traces that have long since disappeared on the geologically active Earth.

Although the image of a stone-picking astronaut is nostalgic, Van Westrenen emphatically advocates further development of robots for geological research. ‘You may miss some things, but a lot of scientific fieldwork is certainly feasible robotically. So I don’t really believe in the idea that people necessarily have to go to the moon for this.’

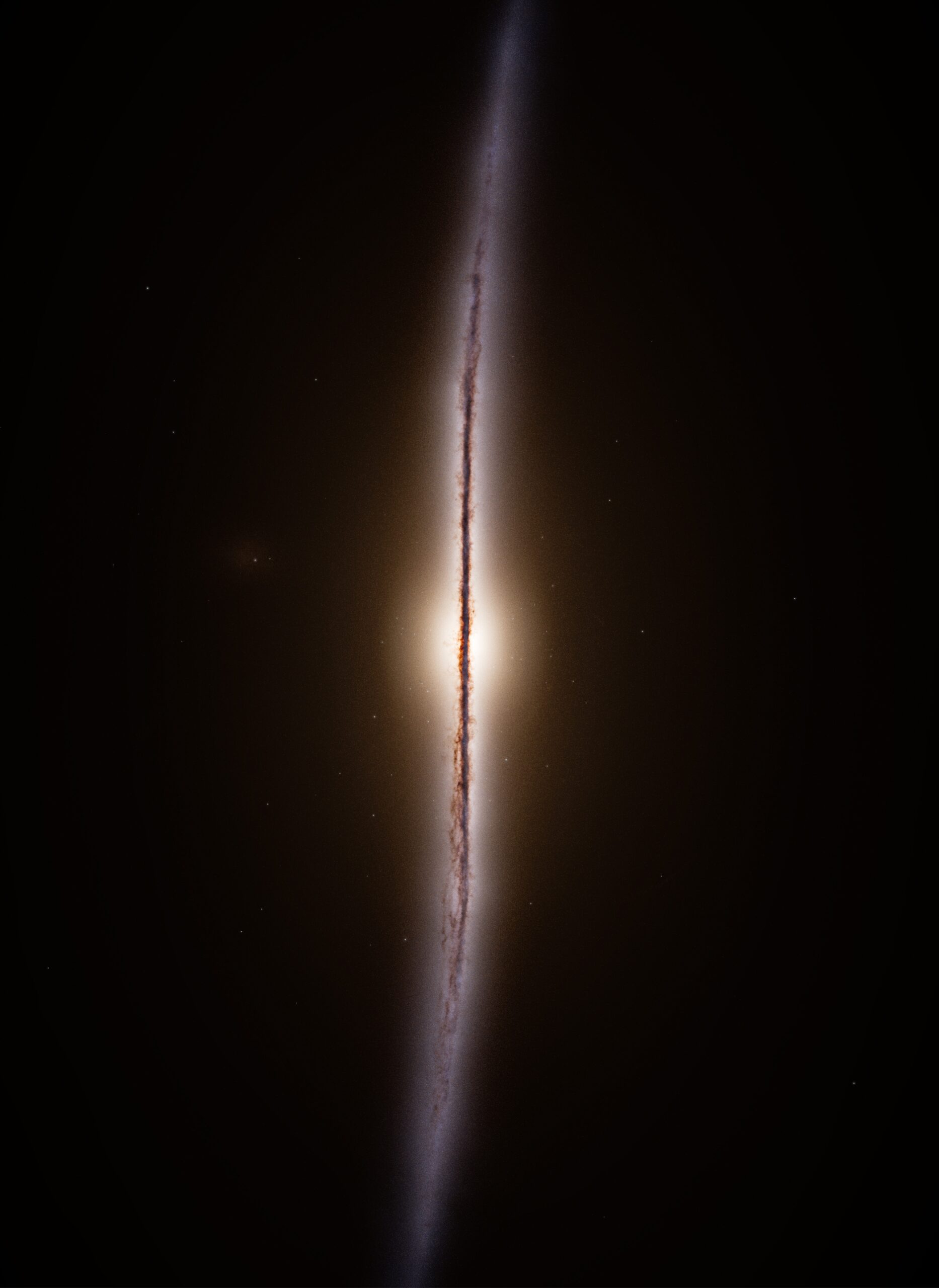

Not all lunar science revolves around rocks and impacts. The far side of the moon, permanently turned away from Earth, is one of the most radio-quiet places in the solar system. A radio telescope there can capture radiation from the young universe, to take a look at the cosmic ‘dark ages’ – a period in which the first stars were still hidden in a thick cloud of hydrogen. This period cannot be observed from Earth: our planet is too noisy in radio waves.

After decades of dedication and lobbying, astrophysicist and NASA advisor Jack Burns managed to realize his dream in 2024: placing the first American radio telescope on the far side of the moon, during the commercial mission IM-1 Odysseus. China previously brought a telescope to the far side with Chang’e 4. Two more commercial lunar missions will follow soon and Marc Klein Wolt is leading the development of a new telescope on behalf of ESA that will travel with an Artemis mission. Thanks in part to Burns’ extensive network within NASA, radio telescopes have remained a priority within the lunar program, despite looming budget cuts. In his opening lecture at Teylers Museum, he emphasized that telescopes on the moon are a difficult task: ‘The lunar night lasts two weeks, so you need enormous charging capacity. Our first mission, for example, carried 70 kilos of batteries. This has to be more sustainable. We must not spoil the lunar landscape while we are using it.’

Burns is an outspoken advocate of the embassy and supports the participation of American parties. ‘We will soon be building major infrastructure, and the radio-quiet back of the moon in particular must be protected – while commercial companies are also eyeing it.’ Moon protection has thus become not only a moral desire, but a practical necessity. According to him, scientific development on the moon requires international cooperation and room for multiple perspectives. ‘The embassy can play a crucial role in this.’

The origin of the moon and the young universe are just a few of the many experiments for which the moon is ideally suited. This allows cosmic radiation to be measured unhindered – something that is impossible on Earth because of our atmosphere. The moon also offers a stable platform for detecting magnetic fields of exoplanets, observing the aurora borealis and australis, and looking deep into the sun during violent eruptions. Astronomer Frans Snik and his team are developing a satellite that will take a ‘super selfie’ of the Earth next year, to compare it with distant exoplanets and thus investigate whether life is possible there. In general, the lunar soil offers a more stable measuring platform than satellites, which makes accurate and long-term measurements possible. The possibilities of the moon extend beyond fundamental science. It is a testing ground for experiments into the effects of radiation on the human body, food production, and the use of moon dust for 3D printing of infrastructure. Much of this knowledge is needed for future habitation of the moon and the rest of the solar system: NASA’s ‘Moon to Mars’ strategy focuses on learning to live on the moon as a springboard to Mars.

For Jasmina Lazendic-Galloway, director of the radio lab at Eindhoven University of Technology, it becomes clear during her lectures and student projects that there is a deeper principle at stake. ‘Students who think about surviving on Mars experience a mental liberation. Where they are limited on Earth, they can start all over again in space. They have to think ahead – twenty to thirty years ahead – because the challenges there are urgent. From that space experience, creative and innovative solutions emerge that we desperately need here on Earth.’

That future perspective sometimes clashes with reality. Van Westrenen: ‘Scientists have long been aware of their responsibility. The idea of protecting Apollo landing sites, or not building the entire moon, is alive in the community. With the growth of commercial plans, the realization also increases: we must not repeat the mistakes we made on Earth. That responsibility is part of good scientific practice.’

During the meeting in Haarlem, lunar science is not yet explicitly central. Discussions are mainly about what the moon means to humanity, how we can best ‘listen’ to it, and what practical impact an Embassy for the Moon can have. Scientists mainly take on an observational role – in the background, but tangibly present as a silent engine and driving force behind the debate.

Museum director Marc de Beyer is delighted that Teylers Museum, the oldest museum in the Netherlands, is hosting this meeting. ‘Teylers has traditionally been a research institute; since our foundation in 1784, we have offered a place where thinkers come together to discuss social issues.’ Whether the Embassy of the Moon will actually be established here is not yet certain, but according to him it is important now to jointly reflect on what we want and how we want to do it. ‘Teylers can play a connecting role in this towards the general public. It is not without reason that our motto is: broaden your horizons and expand your world.’

The initiators are looking ahead with confidence. Marjolijn van Heemstra emphasizes that science and commerce are inextricably linked. ‘That is precisely why scientists must be aware of their impact on the moon. They not only have access to the moon, but also the capacity to think ahead about the consequences. Art is not here for decoration, but as a source of imagination and reflection that can make a difference.’

Marc Klein Wolt agrees: ‘As scientists, we have ‘skin in the game’. We benefit from moon missions, but also bear responsibility for the consequences. It is important to think now about how we can protect the moon, even if that limits our plans. My hope is that in a hundred years people will say: thank goodness they started back then.’

The exhibition Cosmos in Teylers Museum can still be visited until 29 June. This exhibition explores the relationship between man and the universe and shows how imagination helps both artists and scientists to better understand the universe.

https://teylersmuseum.nl/nl/zien-en-doen/kosmos