Red dots hide black holes

“A remarkable ruby:” the title of the article that astronomer Anna de Graaff (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg) and colleagues published in Astronomy & Astrophysics last week. The subject: a tiny infrared bright spot, almost indistinguishable from noise. However, this object, nicknamed The Cliff, can radically adjust our understanding of the early universe. For the first time there is convincing evidence that these dots hide black holes.

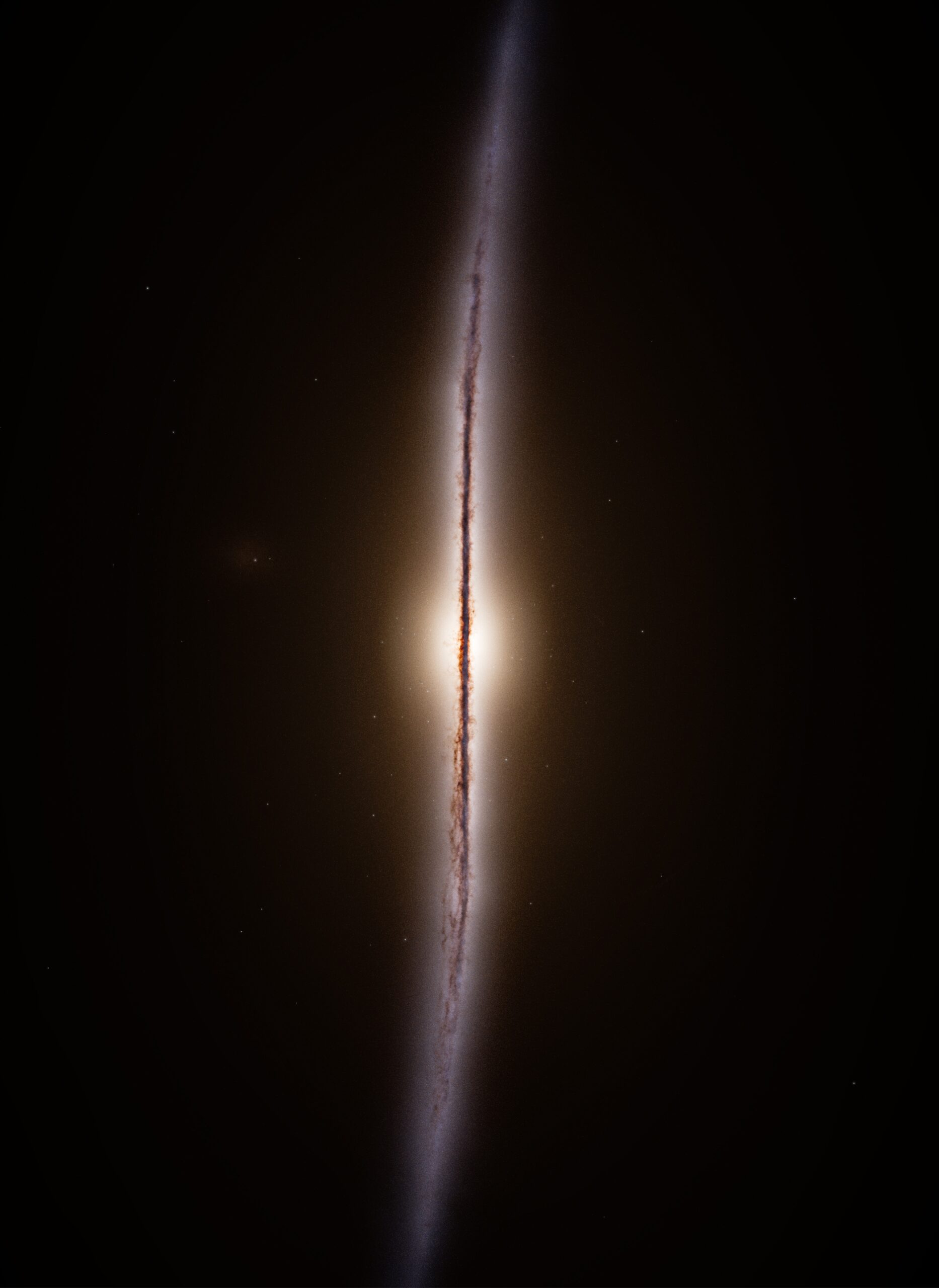

The Cliff is part of a new class compact cosmic objects that astronomers are now affectionately call “small red dots”, a term made by Dutch astronomer Jorryt Matthee (working in Austria). They appear on images of the James Webb spacial telescope (JWST), since they arrived in 2023. Almost a hundred have now been found, good for a few percent of the galaxies surveyed.

The nickname refers to a striking “canyon” in the spectrum: where the light intensity per color normally changes, [the spectrum of] The Cliff makes an abrupt transition – at first almost nothing, and next to it many times stronger. “We could not explain that strong difference with existing models,” says De Graaff.

Researchers rather thought that red dots were either extremely compact galaxies, or active cores full of dust. But in the first case there should be an unrealistic number of stars on a clump, and in the second case an untenable amount of gas and dust would be needed to explain the brightness. De Graaff and colleagues now suggest that The Cliff is not a galaxy, but a so -called ‘black hole star’. “It is actually not a star, but it resembles one,” says De Graaff. If a massive black hole swallows up at a rapid pace, a dense shell of hydrogen can form around it. The gas is so hot by gravity and friction that it starts to shine itself. That glowing “blanket” conceals the black hole, but makes the object visible. “The brightness indicates that there is an enormous mass inside.”

“It is very sound work,” says astronomer Peter Jonker (Radboud University), who was not involved in the research. “The authors have tested all existing statements, and they do not hold up. Their scenario fits surprisingly well.” It is a long unanswered question of how supermassive black holes – billions of times as heavy as the sun, present in the center of almost every galaxy – could grow so quickly in the early universe. “Objects like The Cliff help us to better understand the origin of supermassive black holes,” says Jonker.

Whether The Cliff is unique or exemplary has yet to be confirmed. Earlier observations have already recorded dozens of red dots, good for a few percent of all galaxies found in the data. In the coming years, De Graaff will plow through a lot of new data, including during a research accommodation in the US. In the meantime, almost two hundred papers appeared over the “small red dots” in two years. And according to De Graaff, they remain more than a “remarkable rubies” or cosmic curiosities: “The amount of red dots is consistent with the idea that black hole stars represent a normal growth stage of supermassive black holes.”